Chapter 4. Conservative dentistry, its divisions, purposes and tasks

Conservative Dentistry – part of dentistry, which studies etiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, treatment and prevention of diseases of hard tooth tissues (caries and its complications, non-caries lesions), parodontium and oral mucosa, that is stomatological diseases, which are needed, in the first place, conservative, therapeutic treatment.

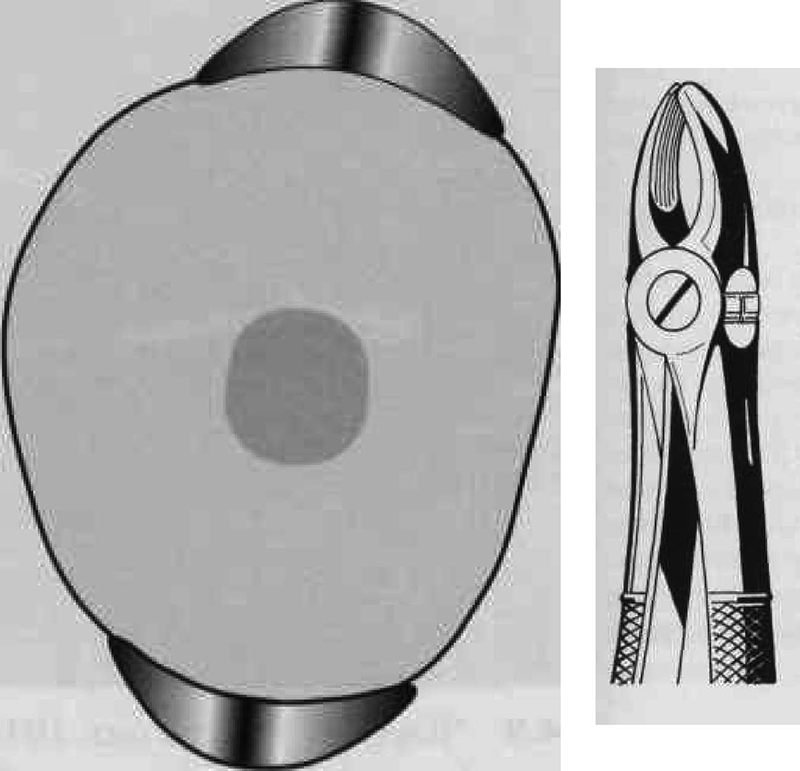

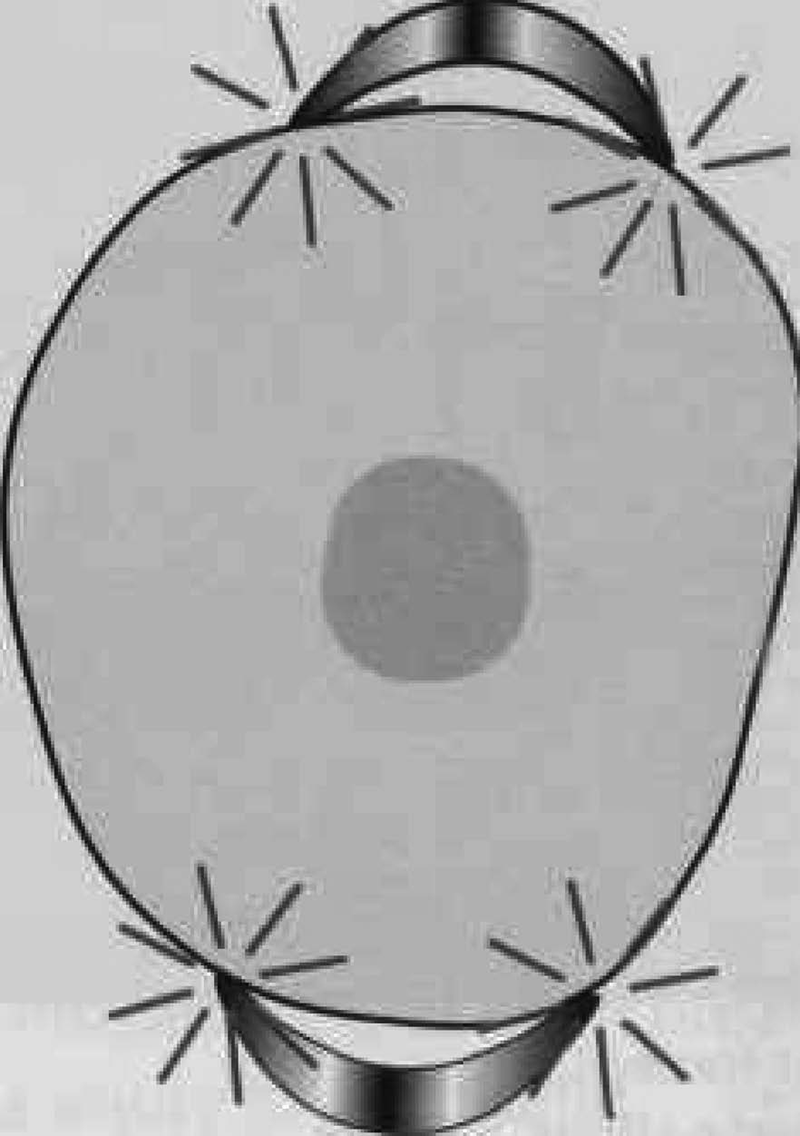

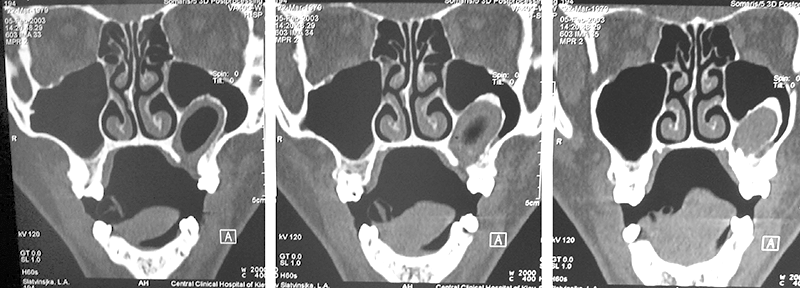

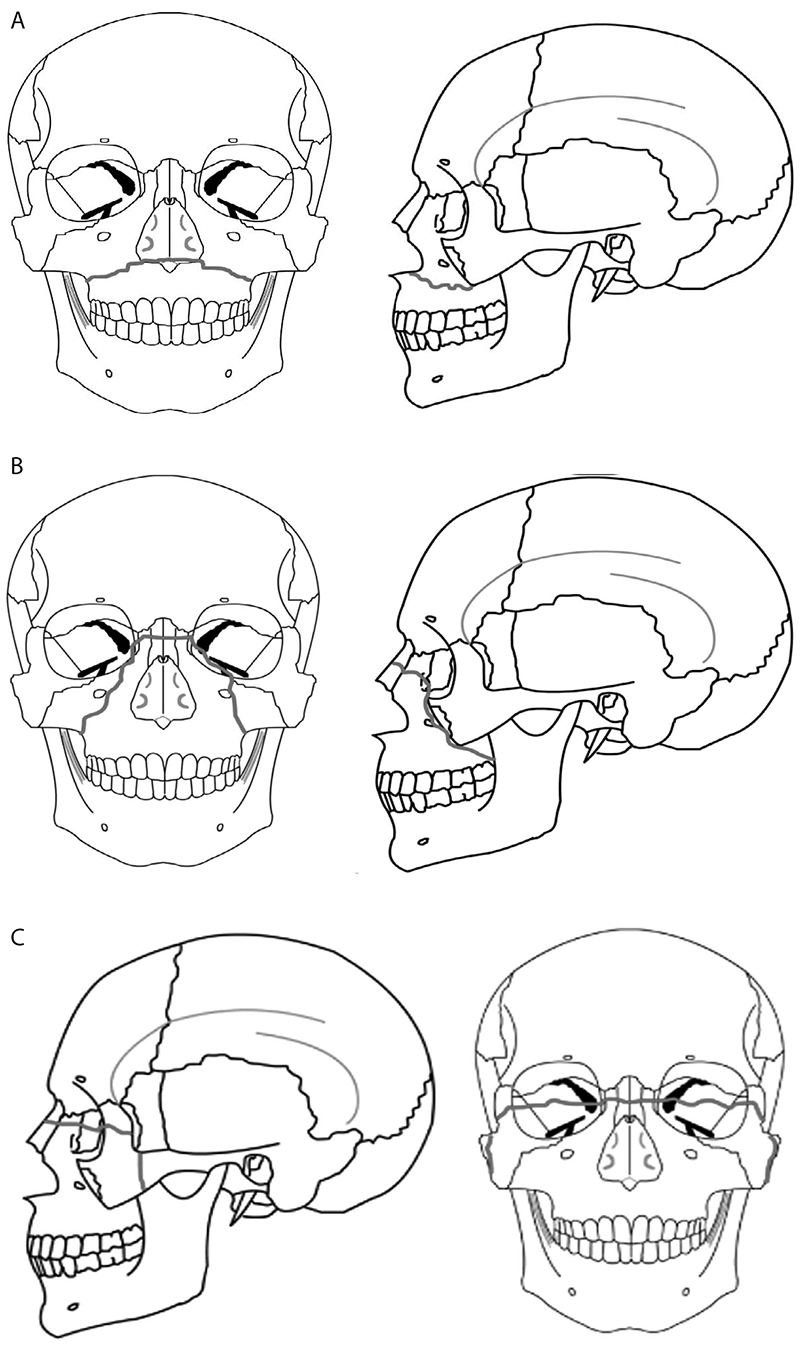

Schema 1

Schema 2

Schema 3

Schema 4

Chapter 5. Noncarious lesions, which appear after the eruption of teeth

Abrasion of the hard teeth tissues

Teeth are obliterated not only by the contact of occlusal surfaces of teeth-antagonists, but also in the section of interdental contact points. As a result of elasticity of the collagenic fibers of periodontium teeth insignificantly move along each other, which is called the physiological mobility (amplitude of 0,1–0,2 mm). In this regard, with age as a result of abrasion the planar contact appears between teeth instead of the point one.

Physiological abrasion is observed both in temporary and in permanent occlusion, for example: temporary and permanent incisors erupt with serrations, which obliterate quite rapidly. In temporary teeth the process of abrasion is more expressed and it barely depends on character of food. When biting and chewing food the abrasion and grinding of the occlusal surfaces of dental crowns occur. The smooth polished areas (facets), whose arrangement depends on the form of occlusion, are forming in superficial layer of enamel.

The degree of physiological abrasion of teeth has risen with the age.

Pathologic abrasion of teeth is the state of their increased abrasion, when the atypical contact areas, surrounded by the sharp edges of the preserved enamel, are formed in the tooth or teeth in a short time. In this case the teeth lose their anatomical form, interrelation in dentitions changes, occlusion reduces and dentitions cannot carry the functional load without subsequent damage of hard tissues.

Clinical picture of pathologic abrasion

Complaints:

- To the increased sensitivity to the temperature stimuli.

- With the deepening of process pain from chemical stimuli can be joined, and then – from mechanical stimuli.

- Subsequently, as a result of intensive postponement of replacing dentine, the increased sensitivity can decrease or disappear.

- In spite of the significant abrasion, in most people the sensitivity of pulp remains or decreases insignificantly.

Objectively:

- Abrasion manifests as disappearance of the cusps of occlusal surface, cutting edges of frontal teeth visually.

- Specific grinding in occlusal surfaces and cutting edges of teeth-antagonists occur.

- Characteristic, smoothly polished, bright surfaces of abrasion (facets), surrounded by protruding sharp edges of enamel are formed. The surfaces of abrasion are different and they depend on the form of occlusion, influence of exogenous and endogenous factors, influence of local mechanical factors.

- Once the enamel is lost completely, considerably process of abrasion of dentine accelerates, which leads to the formation of sharp edges and changes of the anatomical form of teeth. The hard tissues of dental crowns can obliterate almost to the level of gums in the neglected cases of pathologic abrasion.

- With generalized abrasion the lower part of face decreases and occlusion reduces sharply, that causes the disease of temporal-mandibular joint, periodontium and reduction of effectiveness of the chewing of food.

- Surfaces are damaged with caries very rarely, which is explained with the loss of retentional points for the delay of food and microorganisms.

Treatment of pathologic abrasion consists in:

- Elimination of etiological factors.

- Elimination of hyperesthesia.

- Polishing sharp edges of teeth and filling defects.

- Prosthetic treatment to eliminate separate defects and to increase the height of occlusion with fixed or removable denture.

Wedge-shaped defect

It is localized in precervical section. It has the form of the wedge, whose edge is directed toward the cavity of dental crown.

Clinical picture of wedge-shaped defect

Complaints:

- Complaints cannot appear at the initial stages of development of the wedge-shaped defect.

- The sensation of pain or the increased sensitivity from acid, sweet, cold and hot appear with the recession, at the last stages – aesthetical defect.

- Complaints have not been ever, because the slow development of process conduce to deposition of tertiary dentine, but pulp gradually atrophies.

- As a rule, complaints disappear with an even bigger recession of defect, in this case the cavity of tooth is obliterated and it looks as dark point.

- The subsequent progress of defect can lead to the fracture of crown. Rarely defect is complicated with caries.

Objectively: at the early stages of its development wedge-shaped defect does not have a form of wedge, but superficial scratches or thin fissures, or slots are revealed. Then these recesses begin to widen and, reaching certain depth, more and more they acquire the form of a wedge.

Both walls are smooth, shining, polished, unconverted in colour.

Defects are localized on the vestibular surfaces predominantly and very rare – on lingual (palatine). They can be single, but more often – multiple and they are placed on the symmetrical teeth, they develop very slowly.

Treatment of wedge-shaped defect

The general treatment provides for prescription the microelements and vitamins for the purpose of strengthening of structure of teeth internally and the removal of hyperesthesia.

The wedge-shaped defects, whose depth exceeds 2 mm, must be filled (before this course of remineralized therapy is prescribed).

In certain cases, in danger of destruction of the tooth crown the tooth is covered with an artificial crown.

Erosion of hard teeth tissues

This is the progressive loss of hard teeth tissues (enamel or dentine) with unexplained etiology. In contrast to the carious lesions, the appearance of erosion is not related to the influence of microorganisms.

Clinical picture. Erosions are localized on the symmetrical surfaces of central and lateral incisors of upper jaw, and also on canines and premolars of both jaws, they does not occur on incisors and molar of the lower jaw. As a rule, there are no single lesions, usually two and more symmetrically placed teeth are involved.

Since the beginning of development erosion looks as defect of oval form, which is placed in the transverse direction on the most convex part of vestibular surface of crown. The bottom of erosion is smooth, shining, solid. A constant recession and the expansion of the limits of erosion lead to the loss of entire enamel on the vestibular surface of tooth and part of the dentine.

Subjectively. Pains appear rarely or expressed weakly. This is connected with the slow development of process, as a result of which occurs the postponement of replacing dentine. The pains can appear from all forms of stimuli – temperature, chemical and mechanical with increasing depth of lesion. The periods of appearance of pain (active phase) alternate with their absence (stopped erosion).

Treatment of the erosions of hard tissues. It is necessary to take into account the activity of process and character of the associated somatic disease (which is treated by a specialist).

Necrosis of hard teeth tissues

This is unique noncarious lesion, which is developed under the influence of some unmicrobal external factors (acids, ionizing emission), it is characterized with the progressive and irreversible destruction of hard teeth tissues and can to lead to total loss of teeth.

Necrosis is caused by both exogenous and endogenous (disturbance of the activity of endocrine glands, diseases of central nervous system, chronic intoxication of organism) factors. Types of necrosis are: precervical and chemical necrosis.

Acidic (chemical) necrosis appears in people, who work in the manufacturing mostly of inorganic acids, which evaporate and fall into the saliva. In this case the saliva acquires acid reaction and decalcifies the hard teeth tissues. This lesion is possible, but in the mild form, when using 10 % of hydrochloric acid with achylic gastritis. Oral respiration favours to the appearance of acidic necrosis.

At acidic necrosis, at first, frontal teeth are affected, enamel begins to disappear from the cutting edge, and then process passes to the vestibular surface. At first, teeth become matted, then – dull gray, sometimes yellow or brown. The dental crowns become shorter, the cutting edge acquires oval form. Gradually the crowns of front teeth become destroyed to gingival edge, and premolars and molars erase badly.

Typical complaints in patients appear already at the initial stages: the sensations of numbness and soreness in the teeth, the sensation of adhesion of teeth with occlusal contact appear. The phenomena of hyperesthesia can appear. If replacing dentine manages to form, then painful sensation subside.

Treatment consists in:

- elimination of the reason for the acidic necrosis (with hydrochloric acid must drink through the straw);

- remineralizing therapy with the preparations of calcium and fluorine;

- alkaline gargles.

Hyperesthesia of hard teeth tissues

Hyperestesia is the increased painful sensitivity of the hard teeth tissues in response to the action even of insignificant temperature, chemical and mechanical stimuli, which rapidly disappears. Usually these phenomena are constant, but sometimes temporary calming or curtailment of pain (remission) can observe. Sometimes pain can radiate to the adjacent teeth. More often this phenomenon is observed with the pathology of the hard tooth tissues of noncarious origin, and also with the caries and the diseases of periodontium.

Hyperesthesia can be:

- local (it appears from the action of local stimuli);

- systemic or generalized, which appears with neural and mental diseases (psychoneuroses), endocrinopathies, metabolic disturbances, diseases of digestive canal, climax, infectious diseases.

The most important is local treatment of hyperesthesia. These groups of medicines can be used for treatment:

- Cauter medicines.

- Medicines with dehydrating action.

- Medicines with biological action.

- Anesthetics and analgesics.

- Adhesive systems of light-cured composite materials.

Clinical efficiency and complications for home methods of tooth bleaching, dental treatments and preventive measures:

Methods of elimination of external colouring of teeth:

- Microabrasion:

- Removal of a superficial layer of enamel.

- Smoothing of enamel.

- Light reflexion.

- Bleaching.

- Clarification of enamel – (without destroying enamel structure):

- Professional cleaning.

- Sanitation.

- Individual hygiene of oral cavity.

- Bleaching:

- The bleaching agent penetrates into enamel.

- Discharge of О2.

- Oxidation of organic substances, which colouring teeth.

- Denaturation of proteins entering into a pigment.

- Tooth clarification.

Classification of dental bleaching:

- Professional office (surgery) bleaching systems.

- Professional home bleaching systems.

- Home means:

- Teeth bleaching pastes.

- Rinses.

- Chewing gums.

- Bleaching sticks, pencils, varnishes, gels.

Types of bleaching substances

The 1st group – Contains acids.

The 2nd group – Substances discharging oxygen.

The 3rd group – Physical factors intensifying action of the bleaching substances: laser, ultraviolet rays, heat, halogen light.

The 4th group – Combined.

Chapter 6. Dental caries

Dental caries (tooth decay) and periodontal disease are probably the most common chronic diseases in the world. Although caries has been affected humans since prehistoric times, the prevalence of this disease has greatly increased in modern times on a worldwide basis, an increase strongly associated with dietary change. However, evidence now indicates that this trend peaked and began to decline in many countries in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the decline was most notable in certain segments of the population of the United States and Western Europe. The decline in caries in developed countries such as the United States has been most prominent in the upper and middle classes, while the lower socioeconomic classes and rural residents have retained a higher prevalence of tooth decay.

A dental caries (caries dentis, from Latin – caries – decay) is a pathological process which manifests as demineralization and destruction of hard tooth tissues forming carious cavity. Dental caries is an infectious microbiologic disease of the teeth that results in localized dissolution and destruction of the hard tooth calcified tissues.

As a human disease caries is known from deep antiquity, possible information about this illness appeared in hand-written manuscripts already near a 3000 year B. C. An examination of prehistoric crania found in various museums indicated that the percentage of carious teeth ranged from 2 to 7 %. At that time caries yet was not enough widespread illness, but in more late epoch (Middle Ages) its prevalence began to increase. It links with the nutritional changes of people, environmental conditions and mode of life. By the year 1850 there was a rapid dietary change in the direction of increasing consumption of sugar and milled wheat products by all segments of the population. In the XIX century, caries experience in England increased rapidly after 1850. Since the XVII century, caries prevalence increase sharply and in XX century its prevalence in some regions of world is nearly 100 %. Now there are different levels of caries prevalence from 1–3 % in the countries of Western Europe to 80–97 % in the countries of Africa, Asia and former Soviet Union. It is explained by alongside factors: the character of nutrition (above all things excess of carbohydrates in food (sugar and milled wheat products) and relative lack of proteins in the nutritional ration), low concentration of fluoride and other macro-, microelements in drinking-water, social and climate conditions.

In epidemiology studies of estimation of the state of teeth some indexes were used: caries prevalence, intensity, morbidity (increase of intensity for a period of time). The number of individuals in a population having a disease at a particular point in time is known as the prevalence of disease.

Caries prevalence (latitude) is calculated by dividing the number of persons who have caries lesion, filled and extracted teeth (regardless of the number of carious teeth in each of them) by the total number of inspected persons and is expressed in percentages:

The number of persons with new cases of a disease in a population over a given period of time, usually 1 year, is the incidence of the disease.

The most common epidemiologic measure of caries is evaluation of the number of permanent teeth that are diseased, missing, or filled (DMF). Measures of primary teeth are also reported as DMF. DMF may be reported as the number of teeth (DMFT) or surfaces affected (DMFS). This measure is cumulative because it totals the number of restorations and extractions in addition to the number of teeth having active caries.

The index of DMF of teeth is the number of caries – diseased tooth (D), filling (F) and missing because of complications of caries (M) in one inspected person. In determination of this and other mean values of indexes of intensity in a significant number of people their sum divides by the number of inspected people. During determining the index of DMF a tooth which has one or a few carious cavities is considered as decayed or diseased (D), filling – one or a few filling cavities, regardless of their size and condition. If in a tooth there is simultaneously filling and carious cavity, it is considered as caries. In children this index is calculated depending on occlusion: in permanent occlusion there are permanent teeth measured by caries (index of DMF); in primary (milk) teeth – index of df (decay and filling) and in adolescence measured both permanent and primary teeth – DMF + df.

The general condition of human organism, in particular, past and concomitant systemic diseases have a definite influence on intensity of caries. There is higher prevalence of caries in children carrying infectious and systemic diseases. The general changes in immunological reactivity of organism made a considerable influence on caries development.

The status of oral hygiene and quality of teeth brushing is one of important factors in caries development. The regular care of teeth with the use of modern prophylactic and hygienic measures is a very effective method of caries prophylaxis. Up to a point, uneven cleaning of different teeth is expressed in frequency of caries development in separate teeth. Very often caries develops in teeth with very complicated anatomical form of crowns with plenty of pits and fissures.

On the basis of overall caries patterns permanent teeth can be grouped according to their susceptibility to caries, from the most to the least susceptible, as follows:

- Lower first and second molars, upper first molars

- Upper second molars.

- Upper premolars.

- Upper incisors.

- Upper canines.

- Lower premolars.

- Lower incisors.

- Lower canines.

Theories of the dental caries

Dental caries is the best known and most widespread human diseases. In spite of successes attained lately in caries prophylaxis and medical treatment in the countries of Western Europe and North America caries remains the most widespread disease.

The problem of caries development interested many researchers since ancient times. Depending on the degree of development of science and medicine different theories of caries development were presented. Therefore no wonder that to the present time a lot of different conceptions of caries were proposed.

Modern conceptions of caries development

The interaction of three main factors is essential for the initiation and progression of caries: a susceptible host tissue, the tooth; microflora with a cariogenic potential; and a suitable local substrate to meet the requirements of the pathodontic flora. The tooth is the target tissue destroyed in the dental caries process. The cariogenic oral flora, localized on specific sites of teeth, is the agent that produces and secretes the chemical substances (organic acids, chelating agents and proteolytic enzymes) that cause the destruction of the inorganic components and the subsequent breakdown of the organic moieties of enamel and dentin. The local substrate provides the nutritional and energy requirement for the oral microflora, thereby permitting them to colonize, grow, and metabolize on selective surfaces of teeth. The third factor – resistance of the tooth – is obviously important since it determines the overall effect of the attack.

According to the modern conceptions of caries development (E. V. Borovsky et al., 1979, 1982) there are few groups of cariogenic factors. There are factors of systemic character, local and related to resistance of hard tooth tissues. To systemic factors belong non sufficient diet and drinking-water (the especially low contents of fluoride in water), systemic diseases and disorders, extreme unfavorable influences. Local factors are the dental plaques, microflora, disturbance of saliva composition and properties, carbohydrate food debris. Disturbances of resistance of dental hard tooth tissues are related to their inferior structure, defects of chemical composition, unfavorable genetic code (by the hereditary propensity of hard tooth tissues to the caries). It is needed to mean that the separately taken cariogenic factor or their group, affecting a tooth, made it susceptible to influence of direct cariogenic factors (acids), creating, thus, a cariogenic situation. However, only cooperation of different groups of cariogenic factors creates favourable conditions for caries development.

Groups of cariogenic factors

| Systemic cariogenic factors |

Local cariogenic factors: |

Disturbance of tooth tissues resistance: |

| Non sufficient diet and drinking water |

Dental plaques |

Defects of structure |

| Systemic diseases and systemic disorders |

Microflora |

Defects of chemical composition |

| Extreme unfavorable influences |

Disturbances of properties and composition of saliva |

Unfavorable genetic code |

| – |

Carbohydrate food rests |

– |

The systemic cariogenic factors

Non sufficient diet and drinking water. Development, forming and subsequent existence of teeth to a great extent rely on the nutrition of man, disturbance of which results in development of diseases, including dental caries. The most credible cariogenic action is made because of excess of carbohydrates in food, deficiency of mineral salts and microelements in it, soft consistency of food. By numerous clinical investigations in people which ingested many of carbohydrates in diet the considerable prevalence of caries was revealed. Especially it was expressed in the use of sucrose and glucose. They render the most unfavorable action in children, when hard tooth tissues are yet not completely mineralized.

Cariogenic action of excess of di- and monosaccharides in the diet was confirmed as a whole alongside with experiments of caries modeling in animals. It was revealed, that the greatest carogenic effect was rendered by sucrose, to a lesser extent – glucose and then other carbohydrates. Cariogenic action of carbohydrates is more evident at their direct contact with hard tooth tissues in the oral cavity.

Systemic diseases, disorders and concomitant diseases creating a favorable background for caries development. Numerous investigations showed that people with most systemic diseases are accompanied by considerable prevalence and intensity of caries. Different degrees of caries prevalence relies on influence of systemic diseases on the common state of organism and their duration. It is impossible to consider that common diseases directly affect hard tooth tissues, they rather affect them indirectly by means of changes of composition of saliva, rate of saliva flow or through pulp. In some measure this influence is possible by means of change in composition of microflora and hygienic status of the oral cavity. The most unfavorable influence of common diseases on teeth is indicated during their development, mineralization and eruption. In children of different ages with concomitant diseases of internal organs, dental caries develops especially often and is characterized by the acute coarse and numerous lesions of teeth. Thus, these diseases create a background on which unfavorable local cariogenic factors will be easily realized.

Among unfavorable extreme influences on human organism the most damaging action on teeth is rendered by ionizing radiation. It violates activity of salivary glands of oral cavity, diminishes the rate of saliva flow, large amount of dental debris – substantia alba – accumulates on teeth (G. M. Barer, 1972). In future spots of enamel demineralization and destruction develop on these places. Direct damaging action of ionizing radiation, directly on hard tooth tissues, is also revealed.

Local cariogenic factors made direct damaging action on hard tooth tissues. Most cariogenic action both independently and in combination with other factors had dental deposits: dental debris and dental plaques. Dental deposit is rather yellow or grayish-white soft and sticky deposition on the surface of teeth, which is a conglomerate of microorganisms, cells of desquamate epithelium, leucocytes, mixture of proteins and lipids of saliva with the particles of food. Soft dental debris has no permanent inner structure, it is not tightly attached to the enamel surface, thus it can be easily washed off by stream of water or taken off by a cotton pellet. A gelatinous mass of bacteria adhering to the tooth surface is termed dental plaque. Dental plaque is a soft amorphous granular deposit, which is enough tightly attached to the tooth surface, from which it can be removed only by mechanical cleaning with a special instrument or tooth brush. When plaque is small in size it cannot be revealed (if not colored by means of food dyes and coloring agents), in large amounts the mass on the tooth surface becomes grayish or yellow-grey.

Formation of acids in dental debris (dental plaque) and decline of pH takes occur only when carbohydrates enter oral cavity. The microorganisms of plaque fermente sucrose, glucose and fructose easier. The cellular elements of plaque together with protein agglutinative elements provide its porous structure which can pass through itself oral fluid (saliva, food liquids). The microorganisms form extracellular polysaccharides which clog intercellular spaces with plaque and thus promote the accumulation of organic acids in it. Most easily carbohydrates (sucrose, glucose) penetrate in dental plaque, which are revealed in it in the amount directly proportional to their concentration in saliva and duration of application. Simultaneously the plaque prevents the penetration of alkaline components of saliva buffer system, which can neutralize acids. In the abcence of carbohydrates the level of plaque pH usually ranges close to neutral – 7.0. Entering oral cavity carbohydrates cause sharp increase in acidity of plaque, which lasts about 30 minutes reaching the maximum of pH to 5.8–4.5.

After this the saliva buffer systems neutralize the acidic environment in plaque and its pH subsides to the neutral level again. During repeated entering of sucrose enough persistent decline in pH under the dental plaque occurs, this leads to damage of dental enamel.

Dissolution of dental enamel begins when pH = 5.5 therefore this pH level is called critical. Under the plaque the increase in acidity might be more significant. In addition plaque prevents the penetration into the enamel of alkaline components of saliva buffer system, which can neutralize acids and inorganic matters, that constantly enter the enamel with saliva, restoring its mineral structure.

Role of microorganisms in caries development. The considerable role of microorganisms in caries development was confirmed by works of W. Miller.

The highest cariogenic activity was revealed among streptococci, especially Str. mutans. This species of streptococci causes in animals the most rapid caries development with a plenty (to 75 %) of affected teeth. Today the properties of this species of streptococci are studied in great detail and its exceptional role in caries development is shown.

The ability of this species of streptococci to adhesion on the dental surface due to the synthesis extra cell polymers, such as, for example, dextrans. It is necessary to emphasize that other types of cariogenic microorganisms are able to synthesize such polymers of sugars (especially sucrose which enters oral cavity). Such polymers give a possibility to other cariogenic bacteria to be glued to hard tooth tissues (enamel), thus forming a dental plaque matrix.

In carious cavities and saliva in patients with dental caries lots of lactobacilli were revealed. These bacteria have very high acidophilic properties and power to cause caries development in experimental animals. In people with active caries higher contents of lactobacilli in saliva, in comparison with healthy persons, are revealed. On the basis of determining the amount of acidophilic bacteria in saliva a test was developed, the so-called streptococcus or lactobacilli test, which is an indicator of caries activity or susceptibility to caries development.

Acidophilic actinomyces species have a definite role in caries development. They are also selected from carious cavities. The highest cariogenic activity was shown in two kinds of actinomyces species – Actinomyces viscosus and Actinomyces muslundii – in experimental study of actinomyces species in gnotobiotic animal. Actinomyces species take a significant part in dental plaque matrix formation.

In case of appropriate conditions the microorganisms of dental plaque actively ferment carbohydrates, producing acids. Under the influence of cariogenic factors on tooth enamel the processes of demineralization and depolymerization of organic matters occur, as a result appears a caries lesion. A number of anticariogenic factors prevents the action of cariogenic factors: antimicrobial systems of saliva, presence of microelements (especially fluoride) in diet, high buffer capacity of saliva, presence of inhibitors of proteolytic enzymes, intensity of processes of enamel remineralization and its high caries resistance, strengthening of trophic function of pulp and rise of organism resistance.

In studying disease, primary factors (prerequisites), without which the disease process cannot develop, are often not clearly distinguished from secondary or predisposing factors which control the rate of disease progression. Many secondary factors, such as salivary composition and its flow rate, oral hygiene and diet influence the caries process. Secondary factors affect one or several of the following: increase or reduce the tooth (host) resistance to dental caries; increase or decrease the quantitative and qualitative nature of the oral microflora involved in dental caries; increase or reduce the cariogenicity of the local substrate.

Disturbances of properties and composition of saliva. Saliva plays an important role in providing the physiological balance of processes of mineralization and demineralization in dental enamel. With this function the tooth mineralization, “maturation” of enamel after tooth eruption is carried out, optimum composition of enamel and its remineralization after the damage or disease are supported. Saliva has the protective function of organs of oral cavity from damaging action of factors of external environment and cleansing function, which consists of permanent mechanical and chemical cleansing the oral cavity from food debris, microorganisms, etc.

The saliva reaction (pH) influences on the degree of saliva hydroxyapatite supersaturating: with reduction of pH it sharply goes down. Supersaturating of oral liquid remains only to pH 6.0–6.2 (critical level of pH), and with further acidification it slumps and saliva becomes unsaturated with hydroxyapatite. Usually the reaction of oral fluid lies within the limits of pH 6.5–7.5 and on average it is 7.2, therefore it is neutral or low alkali. Saliva contains a very power buffer system with big capacity. It allows to support the neutral reaction of environment of oral cavity constantly. Therefore the decline in saliva pH, lower than the critical value 6.2–6.0, is marked only locally: in dental debris and under dental plaque. The decline of saliva pH is marked after entering oral cavity by carbohydrates. Reduction of secretion of saliva (hyposalivation) or almost complete cessation of its flow (xerostomia) is accompanied by decline of pH and sharp increase of caries development.

The use of carbohydrates with food causes hyperglycemia, hyposalivation, increase of saliva oxygen absorption and saliva P/Ca coefficient. In people which use a plenty of carbohydrates such changes in saliva occur during practically all day long. Carbohydrates stimulate acidogenic activity of microorganisms in oral cavity (“metabolic explosion”) because of what the quantity of organic acids in saliva significantly increase – in 4-5 times – in comparison with normal condition. All these changes promote in such persons susceptibility to caries which is often numerous and active.

Food debris, accumulated on teeth and in interdental spaces, have pronounced cariogenic effect. Staying saved in retention areas for a long time, they become a breeding ground and material of which microorganisms can produce acids. The most essential value had carbohydrates, especially sucrose and glucose. Carbohydrate food debris can easy transform not only in acids, but also in dextrans, levans, which play a considerable role in forming dental plaque and its attachment to the teeth surface. The sufficient thickness of food debris also prevents the penetration of components of saliva buffer system through them, that additionally creates conditions for accumulation of acids under them.

Defective structure and resistance of hard tooth tissues

Defective structure of hard tooth tissues. An independent factor, which influences on teeth susceptibility or resistance to caries, differs in disturbance of hard tooth tissues structure. This can be the definite peculiarities of chemical composition of enamel apatites, presence of different substitutions in the crystals of apatites, correlations of different inorganic ingredients in its molecule, violations of the P/Ca coefficient. Rightness, regularity of enamel structure of protein matrix and its properties, ability for polymerization and connections of calcium and phosphorus, its co-operation with inorganic phase of enamel have great value. Presence or absence of defects in enamel structure, its density, regularity of structure, size and number of structural violations, density of crystals and rods packing, presence of tufts and lamella and their location, degree of enamel structure maturity and their saturation with calcium, phosphate and fluoride influence on caries resistance at tissular level.

Tooth chemical composition connects with its structure very tightly and has almost the same value in caries development. For example, high mineral concentration determines high density of enamel structure which determines its resistance to caries development. Caries resistance areas have higher contents of fluoride, molybdenum, strontium, selenium, phosphorus and vice versa caries-susceptible areas have lesser. Disturbance of biochemical composition of hard tooth tissues and metabolic processes, that determine caries-susceptibility, can be realized in a caries lesion only in cooperation with other cariogenic factors.

A certain place among cariogenic factors is occupied by unfavorable genetic code that is heredity. It is known, that there is a definite hereditary susceptibility to caries development, although other authors explain it by similarity of food characters. However application of modern methods of genetic analysis allows to reveal a lot (to 16) of genes which are responsible for caries development (C. Chain, 1968). It was supposed that genetic susceptibility to caries development will be realized, mostly, through proper structural features of hard tooth tissues, chemical composition of saliva, some features of metabolic processes in organism.

The above-mentioned cariogenic factors (both general and local) can be expressed in other degree. Caries development is possible at enough different variants of their co-operation, for example, at strong disturbance of tooth structure, small diet violations and a little amount of acidophilic microorganisms in oral cavity are enough to cause dental caries. Thus, under appropriate conditions the cooperation of cariogenic factors becomes possible and as a result caries develops.

Classification of caries

Clinical features of caries are enough various: from a chalky white spot on the surface of enamel to an expressed destruction of hard tooth tissues. These numerous forms of caries, per se, are stages of tooth destruction changing each other consistently (if untreated). The progress of caries process leads to destruction of entire thickness of hard tooth tissues, perforation of pulp chamber and development of inflammation of pulp (pulpitis) or periodontal ligament (apical periodontitis). Therefore pulpitis and apical periodontitis, another tissues of maxillo-facial region, which arise because of caries process, are called caries complications.

Depending on the depth of caries lesion of enamel and dentine, caries is divided into superficial, middle and deep. Depending on the caries course, acute (rampant) and chronic caries are distinguished.

Incipient caries (caries incipience). A characteristic feature is development of demineralization on the enamel surface. As a result incipient white spot lesions and stained, roughened, partially remineralized incipient lesions of enamel develop. A carious cavity in enamel is forming.

Superficial caries (caries superficialis) – there is a carious defect in enamel, dentino-enamel junction is not destroyed by caries process.

Middle caries (caries media) – carious cavity in dentin is formed: in mantle dentin. This layer of dentin is juxtaposed with enamel and converted into the initial layer of dentin from the basement membrane.

Deep caries (caries profunda) – carious cavity in mantle dentin is formed: in circumpulpal dentin. This layer of dentin is localized very close to pulp. The carious cavity can divide from the pulp chamber only very thin partition or only the layer of secondary dentin.

Clinical feature of caries

Incipient caries. Patients complain of spots (white, chalky white, opaque or pigmented), rarely of feeling insignificant sensitiveness, sorenesses of the mouth from different irritants, mainly chemical (sour, sweet).

In the acute (rampant) course on the limited areas of dental enamel the opaque, deprived of natural transparency, chalky white spots appear. At first, spots are small, but, gradually increase in size. They are often located on occlusal surfaces in retentive points: pits and fissures of occlusal surfaces of teeth, cervical areas. In children they are often localized on a vestibular surface and cervical areas. For the best revealing of caries spots it is recommended to remove debris from the spot surface and dry up the tooth crown: intact enamel saves its natural transparency and brilliance, while the surface of caries spot loses transparency and becomes opaque. When probing a roughness, insignificant pliability and painfulness of their surface can be revealed.

The histological features at an initial caries are characterized by development of different degrees of enamel demineralization. In enamel section the body of caries lesion has the form of of a triangle with the basis directed to enamel surface. In the study in the polarized light depending on the structure changes in enamel lesion a few areas are distinguished. The most demineralized is subsuperficial lesion layer, which is covered with mineralized superficial enamel layer. This interesting phenomenon is explained by remineralization processes of carious lesion by the mineral components of saliva. If oral fluid is unable to provide remineralization of the demineralized enamel area, rapid development of caries lesion occurs.

Superficial caries. In some period of time in the center of carious spot the superficial layer of enamel loses the integrity and defect appears in enamel. At acute superficial caries patients complains of insignificant pain, more frequent of feeling soreness of the mouth and affected tooth, caused by chemical irritants, which at once disappear after cessation of irritant actions. Sometimes shot-term pain from thermal and mechanical irritants occur, more often in place of localization of carious lesion.

At the examination of tooth in the area of chalky white color a lesion of a shallow enamel defect (cavity) is determined, placed within the enamel borders. The enamel wall with lesion is softened, yellow-grey and a little sensible when probing. Sometimes it can be only rough surface, but after removing the softened enamel surface the lesion (cavity) is found.

The chronic superficial caries course is mainly painless. Insignificant pain from chemical irritants rarely occurs. But it disappears immediately after cessation of irritant action. A small enamel lesion (cavity) with enough dense yellow-brown or brown enamel walls is revealed on the enamel surface. The cavity has a wide, exposed inlet without overhanging margins. Probing of carious defect is practically painless. When superficial caries is localized in fissures the margins of lesions remain undamaged.

Superficial caries is diagnosed on such grounds: a) patient’ complaints about short-term painful feeling mainly from chemical irritants; pain disappears after cessation of irritant action; b) revealing of shallow carious cavity, located within enamel borders, or of fissures pigmentation on occlusal surface, in which the softened demineralized enamel is revealed when probing; c) painful preparation of hard tooth tissues especially at the dentinoenamel junction.

Middle caries (caries media). After destruction during the pathological process of dentinoenamel junction caries quickly begins to spread to the dentine. Middle caries (caries media) is pathological condition, when a carious cavity is located in mantle dentin. Patients with acute middle caries often complain about painful feeling. More often the pain has weak intensity and appears only under the action of irritants: chemical, thermal, mechanical. On the tooth surface there is a chalky white carious spot with the enamel defect in a center. Examination of the cavity is difficult because of its narrow inlet. The cavity usually has a depth of 1,5–2 mm, it is filled with food debris and softened dentin. Complete examination of carious cavity is possible only after removing of overhanging chalky white enamel margins with special instruments (burs, excavators). The cavity is wider near the dentinoenamel junction and it is narrowing towards the pulp gradually. The softened dentine which covers the cavity, is grey-white or yellow, rarely – pigmented. The degree of dentine softening depends on the activity of caries process: at acute (rampant) caries the hard tooth tissues are more softened like a cartilage, at chronic course it can be harder and pigmented. Probing of carious cavity is practically painless except the dentinoenamel junction.

Chronic middle caries has practically little clinical symptoms. In some cases weak pain can occur because of action of chemical, rarely thermal and mechanical irritants and it disappears at once after their cessation. When examining the carious cavity a rather wide inlet is revealed, it is located in mantle dentin, the depth of cavity is 1,5–2 mm depending on the surface of the tooth. The carious cavity is covered with rather dense pigmented dentin, floor and walls of the cavity are painless when probing. During electric pulp testing (electroodontodiagnostic method) the pulp reacts on the current strength of 6–12 mcA.

Deep caries (caries profunda). It is characterized by formation of carious cavity which affected almost all layers of dentine practically to pulp and it is located in circumpulpal dentin. Patients with acute deep caries complain about causal pain which appears because of action of thermal, mechanical, chemical irritants and disappears after their cessation. Inserting into the carious cavity of cotton tampon with hot (no more than 50 ºC) or cold water, and also ether is usually accompanied by sharp pain reaction, however, pain disappears after the removal of irritants from the cavity. Carious cavity is located within the limits of circumpulpal dentin with the overhanging margins of enamel. Enamel around the inlet has softened chalky white color. The carious cavity is filled with grey-whitish or yellow softened dentin. When probing a painful area on the cavity floor and dentinoenamel junction is revealed. Often it is the places of projection of pulp horns, which directly react on irritants; however, perforation of carious cavity is not observed. At acute deep caries, probing of caries cavity floor must be made very carefully. At the points of pulp horns projection the dentinal wall is very thin, the dentine is softened and can be easily pierced with a probe and injure pulp. It is accompanied by sharp pain and a blood drop appears in the carious cavity.

At the chronic deep caries there can be no complaints of pain, while insignificant, brief pain after thermal, chemical and mechanical irritants can be revealed. Defect of hard tooth tissues is located in limits of circumpulpal dentin, rather large in size, occupies considerable part of tooth crown. Cavity is wide opened (the overhanging edges of enamel are broken off because of their fragility). As a result, the transversal sizes of cavity exceed its depth. Walls and floor of carious cavity are filled with rather dense, pigmented dentin, but without sclerotic brilliance. Pigmentation of its walls and floor has enough wide spectrum – from yellow-brown to brown and even almost black color. Probing of walls and floor of the cavity is painless, because of development of well expressed areas of transparent and secondary dentin under them. Surface of the carious dentin is rough when probing. The development of such cavity continues for years.

Medical treatment of dental caries

Medical treatment of caries consists of a number of measures of general and local character depending on the stage of development of pathological process and character of its course. On early stages (caries incipience) this complex of measures is directed on the removal or reduction of effect of demineralized factors action, and also on renewal (remineralization) of partly demineralized hard tooth tissues. When the pathological process spreads to enamelodentinal junction, a dentine strikes and a carious cavity appears, conservative (remineralization) therapy can not result in success. It is connected with the fact that hard tooth tissues do not possess property to regenerate the primary form in the area of carious lesion. Therefore for local medical treatment of carious cavities their preparation is used, with the subsequent filling of cavity and renewal of anatomic form of tooth by filling material.

None of varieties of restoration treatment of dental caries can be complete “curing”. Destroyed with caries the hard tooth tissues (and adjoining areas of healthy enamel) are not substituted for newly formed enamel and dentin. Besides, there is no restoration material capable to protect hard tooth tissues from further destructive caries processes during all life. Tooth filling is only symptomatic treatment which does not eliminate the etiologic factors of dental caries.

Therefore the prevention of carious lesions development (prophylactic measures) is the basic principle of caries treatment, than – necessary medical treatment (remineralization therapy) and, in the last turn, forced measure – filling the carious cavity with filling materials, conducted along with the measures of the secondary caries prophylaxis.

Thus, now there are two main methods of local caries treatment:

- caries treatment without preparation and filling – remineralization therapy;

- operative caries treatment by the operative preparation of demineralized hard tooth tissues with the subsequent filling of carious cavity.

The choice of treatment method depends on the stage of caries development, activity of caries (acute or chronic), localization of carious cavity, age and general condition of patient.

Conservative medical treatment (remineralization therapy) of dental caries can be conducted only on the stage of absence of a cavity in hard tooth tissues, that is at caries incipience, when anatomic integrity of enamel is not broken.

In general for local remineralization therapy of incipient caries such groups of medications can be used:

1. Means, which influence on mineralization of enamel (they restore and complement ions which are absent in the crystals of enamel at caries; influence on kinetics of mineralization, ect).

2. Means, which prevent adsorption of organic matters (acids, toxins and other products of vital functions of microorganisms) on the surface of hard tooth tissues (desorbents, hydrofobic pellicle coverages, sealants).

Various preparations of fluoride, calcium, phosphor-calcium combination, complexes of mineral components (remodent), etc, are referred to the first group. Their introduction into the demineralized enamel areas renders assistance in remineralization, renewal of mineralization degree, increases stability of enamel to action of acids and other cariogenic factors. Preparations of fluoride, pectins, natural and synthetic varnishes, and various fissure sealants prevent adsorption of organic matters.

Preparations of calcium and fluoride are often applied for remineralization. The usage of different calcium salts is pathogenetic reasonable with its predominance among other mineral elements in the structure of hard tooth tissues apatites (hydroxyapatite, etc.). Efficiency of fluoride preparations application is conditioned with its influence on some mechanisms of pathological process.

There was proposed application and electrophoresis of 1 % solution of sodium fluoride for medical treatment of initial caries. The surface of teeth is carefully cleaned from dental plaques with the help of excavators or special brushes and pastes. Teeth are isolated from saliva and a cotton tampon or a small gauze serviette moistened with 1 % solution of sodium fluoride is put on the carious lesion. Duration of application is 15–20 minutes, during this time the cotton tampon with sodium fluoride solution is been changing 3–4 times. The course of medical treatment consists of 15–20 everyday application. More effective is introduction into enamel of fluoride with electrophoresis with 1 % solution of sodium fluoride that provides more deep penetration of fluoride ions in hard tooth tissues. Duration of procedure is 10–20 minutes, the course of medical electrophoresis treatment is 10 attendances.

Medical forms, which provide adhesion of fluoride preparation to the enamel, in particular, fluoride varnishes and gels, are developed for prolongation of fluoride action on hard, tooth tissues. Fluoride varnish is a composition of natural yellow resins of viscid consistency which contain 1–5 % fluoride (as often as sodium fluoride). For example, widely applied in practice fluoride varnish contains 5 % sodium fluoride, 40 % silver fir balsam, 10 % shellac, 12 % chloroform, 24 % ethyl alcohol, etc. A number of various fluoride varnishes is proposed, for example, “Fluor Protector”, “Duraphat”, “Bifluorid 12” (VOCO), “Belagel F”, “Belak F” (“VladMiVa”, Russia), etc. Teeth are isolated from saliva, dried out and on the area of demineralized enamel the fluoride varnish is applied, which dries up on the enamel surface during 4–5 minutes. Than the patient is recommended not to eat for 2–3 hours, to save this varnish film. It remains on the tooth surface for a few hours, that provides the long contact of fluoride with tooth enamel. Fluoride gels are also applied. In general the course of remineralization therapy consists of 15–20 attendances which are carried out every day or on alternate days.

For local medical treatment of initial caries the preparations of calcium are widely used: 10 % solution of calcium gluconate or calcium chloride, 5–10 % acidified solution of calcium phosphate, 2,5 % solution of calcium glycerophosphate. They are applied for applications and electrophoresis (the ions of calcium enter from a positive electrode – anode). The course of medical treatment depends on caries activity, number of carious lesions, etc., and it can achieve 15–20 applications or 10–15 procedures of electrophoresis. Efficiency of remineralization action of calcium preparations is multiplied at their combination with phosphorus preparations. As a remineralization preparation the solution, which contains 11 % calcium and 22 % phosphorus is also used (A. Iraig, I. Iraham, 1975). Calcium-phosphate gels, which provide long remineralization action, were also developed. As a remineralization mean fluid containing synthetic hydroxyapatite can be used.

As a result of the effectively carried out medical treatment (remineralization therapy) the demineralized areas of enamel diminish in sizes or disappear. It is possible transition of caries in its stationary form: in such cases a carious spot changes the color from chalky white to yellow or brown and some diminishes in sizes. To determine the effectiveness of the treatment the remineralization teeth are painted with dyes, for example, with 2 % water solution of methylene blue. If renewal of the degree of mineralization of enamel mineral structures is happened, the area of caries spot is not painted with methylene blue or the degree of staining is insignificant.

It has long been recognized that pits and fissures, especially on occlusal surfaces of teeth, are the most susceptible to caries. At localization of carious spots in fissures of molars and premolars one of the effective methods of medical treatment of such caries is sealing pits and fissures with sealants. Pit-and-fissure sealants provide safe and effective method of prevention of caries. Sealants are the most effective in children when they are applied to the pits and fissures of permanent posterior teeth immediately after eruption of the clinical crowns.

For fissure sealing a number of the most various preparations is used. For filling microspaces which appear in enamel at incipient caries the simple chemical matters can be used: silver nitrate, zinc chloride. Sealing cements (polycarboxylate, silicate, polyacrilic, glass-ionomer cements), composites (chemical and light cured) are actually used for fissures. For greater remineralization action the fluoride preparations are introduced into sealant composition.

At chronic course of incipient caries (yellow and brown carious spots) remineralization therapy is not obligatory. Except for preparation, at chronic caries the pigmented spots can be deleted with the method of enamel microabrasion. Enamel microabrasion is the controlled deleting of enamel, which changed its color, with the mixture of pumice powder and acid, usually hydrochloric acids. For this purpose special device is used – “HANDIBLASTER” (“Bisco”). This method is effective for medical treatment of superficial enamel discolorations (white or brown spots) caused by orthodontic treatment. The device sprays abrasive powder (usually aluminum oxide) on the surface of the tooth for preparation or treatment of the tooth surface before filling.

Operative caries treatment (filling)

During operative caries treatment and filling carious cavity such requirements are recommended to fulfill:

- Completely remove the hard tooth tissues, destroyed by caries, under sufficient anesthesia.

- Create the most convenient conditions for firm and reliable fixations of restorations in prepared carious cavity.

- Unite antiseptic processing with careful drying of prepared hard tooth tissues.

- Rationally select filling material according to classes of carious cavity and properties of restorative materials, following the rules of its manipulation and inserting into carious cavity.

- Grinding, finishing and polishing of the restoration.

In caries treatment such steps are distinguished:

- preparation of oral cavity;

- anesthesia;

- preparation of carious cavity (tooth preparation);

- application of isolating or curative liner;

- filling;

- modeling,

- final grinding, shaping and polishing of the restoration.

In general, the objectives of tooth preparation are to: (1) remove all defects and provide necessary protection to the pulp; (2) extend the restoration (carious cavity); mastication the tooth or the restoration or both will not break and the restoration will not be displaced; and (4) allow for esthetic and functional placement of restorative material.

General rules of tooth preparation:

- Pain control: local anesthesia, analgesia (inhalation sedation), hypnosis.

- Opening and widening the carious cavity.

- Necrectomy.

- Forming and shaping the cavity.

- Beveling enamel margins.

The conventional preparation design is typical for amalgam restoration and includes the following characteristics: (1) uniform pulpal and/or axial wall depths; (2) cavosurface margin design that results in a 90-degree restoration margin; and (3) primary retention form derived from occlusally converging vertical walls.

Clinical techniques of filling carious cavity:

- Antiseptical rinsing of oral cavity.

- Isolation of operating site (rubber dam, cotton rolls).

- Drying the carious cavity.

- Using traditional liners or bases to protect the pulp (up to DEJ).

- Placement and condensing the filling material.

- Contouring of restoration and correction of occlusion.

- Shaping and polishing of restoration (when using amalgam – after 24 hours on next visit).

Isolation of the operative field can be accomplished with a rubber dam or cotton rolls, with or without a retraction cord. Regardless of the method, isolation of the area is imperative if the desired result of restoration is to be obtained. Contamination of cavity enamel or dentin by saliva results in significantly decreased bond of filling material (composite), likewise, contamination of the composite material during insertion results in degradation of physical properties.

When zinc phosphate, glass-ionomer, or polycarboxylate cement bases are used, tooth depth and properties of prior liners determine the technique of placement. When there is known or suspected exposure to the pulp, it must be protected against forcing material into the pulp chamber. Therefore it is essential to either first use calcium hydroxide cement in adequate thickness or nonpressure technique for placing an overlay base.

The filling of carious cavity (e.g. glass-ionomer cements and compomers). Dry the prepared carious cavity of tooth but do not desiccate. The powder/liquid ratio is 2 scoops to 2 drops. Tumble the powder before dispensing. Mix the powder and liquid rapidly for 30 seconds. Place the mixed cement in the carious cavity. A gel state is reached after 1 minute, after which the excess cement can be removed.

The filling of caries cavity (e.g. composites). Once the tooth preparation was completed, the prepared tooth structure is prepared for composite insertion and shaping. Treating the prepared tooth for bonding requires etching and then application of an adhesive if only enamel is prepared, or primer and adhesive if the composite will be bonded to the dentin as well as enamel.

If liquid etchants are used, they are applied with small cotton pellets, foam sponges, or special applicator tips or microbrushes. The acid (liquid or gel) is gently applied to the appropriate surfaces to be bonded, keeping the excess to maximum of 0.5 mm more than expected extent of the restoration. An etching time 15 seconds – for both dentin and enamel is considered sufficient. For enamel-only preparations, 30 seconds is considered optimal. The area is then rinsed with water.

Once enamel (and dentin) is etched, rinsed, and left appropriately moist, the primer is applied to both surfaces. Most contemporary bonding systems combine the primer and adhesive into a single bottle, allowing only a one-time application. If this is the case, it is applied to the moist etched surfaces.

Inserting the Composite. The composite restoration is usually placed in two stages. First, bonding adhesives are applied (if not already placed during the procedures of etching and priming enamel and dentin). Second, the composite restorative material is inserted. With newer bonding systems the adhesive may be combined with another component of the system, mostly the primer. Therefore, as usual, etching and priming the prepared tooth structure and placing the bonding adhesive should be done according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Starting in the most remote area of anterior tooth preparation, the composite is steadily injecting, ensuring that the tip remains in the material while slowly withdrawing the syringe. If the area is large, the light-cured composite is placed in 1 to 2-mm thicknesses, with each increment being cured per manufacturer’s instructions. Usually a hand instrument is used to adapt the composite to the preparation after each syringe injection of material. When curing, the light should be kept as close to the material as possible. If using a hand instrument insertion, a small amount of the composite is carried to the remote area of the preparation and condensed and cured; then more composite is placed and cured with care to adapt it well to the internal preparation walls. The preparation is filled to slight excess so that positive pressure can be applied by the matrix strip.

Following insertion and polymerization of the composite material, the matrix and wedges are removed. If correction is needed, it should be accomplished at this time, because any additions will bond satisfactorily to the uncontaminated, oxygen-inhibited surface layer of the composite material.

Contouring can be initiated immediately after the light-cured composite material has been polymerized or 3 minutes after the initial hardening of self-cured material.

Polishing the contoured composite restoration is done with very fine polishing discs, fine rubber points or cups, and/or composite polishing pastes. Although conventional finishing techniques produce a smooth surface texture with microfill composites, a higher luster can be obtained by using discs, rubber points, or cups, all of which are specifically made for polishing these materials.

Systemic caries treatment. Dental caries is a disease which attacks the dental hard tissues by demineralising enamel. If oral conditions are favourable then this demineralisation can progress from the outer enamel layer of the tooth into the softer underlying dentine, resulting in decay. Dental decay is more common in individuals who often dietary intake of sugars (fermentable carbohydrates). Frequency of intake of carbohydrate is more predictive in the decay process than the absolute amount.

A number of nutritional factors, which may be factors in growth and development such as Vitamins A and D, water hardness and proteins, are hypothesised as potentially linked to dental caries. However, there is little evidence to demonstrate that systemic effects of poor nutrition increase the risk of dental decay, and it is generally accepted that while diet can have a profound local effect on erupted teeth, it has much less effect while the teeth are forming. The diet-caries relationship therefore needs to be evaluated not only against the quantity and type of fermentable carbohydrate consumed, but also against several background factors including intake pattern, total food intake, salivary secretion rate, plaque composition and use of fluoride.

Although the type of sugar consumed is an important factor in development of caries, the frequency of sugar consumption is of greater significance. It has been accepted that the frequency of ingestion of sugar-containing foods is directly proportional to caries experience: that was found that children with caries have snacks between meals approximately four times each day. Children with caries have a high frequency of sugar consumption, not only in fluids given in the nursing bottle, but also in sweetened solid foods. Increased frequency of eating sucrose increases the acidity of plaque and enhances the establishment and dominance of aciduric Mutans Streptococci. It is logical to suppose that partial substitution of sugar in the diet can lead to reduction in the total sugar consumption. The low caries rate in children was associated with total intake of sugars of 10 kg per person per year (about 30 g/day), but caries development increases steeply with intakes of 15 kg upwards (WHO, 1990).

Numerous studies show the prevalence of the disease as to affect up to 70 % of the childhood population, especially in socio-economically deprived population. Inadequacy of the host’s immune-defences may play a role in the acquisition of carious lesions.

Foods and food components that have anticariogenic properties are sometimes referred to as “cariostatic factors”. Despite being one of the main sources of sugars in the diet, milk is anticariogenic. The sugar in milk is lactose, which is the least cariogenic sugar, and milk is also known to contain protective factors. The cariostatic nature of milk can be attributed to the presence of calcium, phosphate, casein and lipids. Calcium and phosphate are present in cow’s milk in high concentrations (125 mg and 96 mg/100 g respectively) and are able to prevent enamel demineralization. Consumption of cheese increases oral pH by stimulating salivary flow and raises plaque calcium concentrations, both of which protect against demineralization.

Tea also contains polyphenols, in addition to fluoride and flavanoids. Tea extracts have also been shown to inhibit salivary amylase activity. The protective effect of tea may be associated with fluoride or antibacterial action of polyphenols, or both.

Dietary control is an important part of caries prevention. Successful dietary advice at the level of an individual (advice that leads to caries reduction) requires effective advice, adequate provision and resources to provide advice, and patient compliance. However, efforts at this level need to be reinforced with population-based strategies for caries prevention.

The arrows in the preventive non-operative quiver are:

- plaque control;

- use of fluoride;

- dietary modification.

The way in which each of these modalities is used will depend on the circumstances of the individual patient.

Since carious lesions form as a result of the metabolic processes in the dental plaque, good plaque control must be the cornerstone of preventive non-operative treatment. Teeth should be brushed regularly, at least once every day with a fluoride-containing toothpaste. The brushing interferes with the growth of the biofilm and the fluoride application retards lesion progression. The quality of cleaning, rather than the frequency, seems to be of prime importance.

No change in diet should be suggested for a caries-inactive patient, but the dentist should still make the patient aware of how changes in diet (e.g. frequent sugar attacks) may pose a problem if the oral hygiene is poor.

Complication of the caries: pulpitis and periodontitis

Pulpitis

Progressive caries destruction of hard tooth tissues without treatment leads to penetration of microorganisms and toxins into pulp. As a result – developed pulp inflammation (pulpitis) and apical periodontitis. So these diseases are called caries consequences.

The inflammation of pulp – pulpitis, occurred in 14–25 % of cases among other dental diseases. Character of pulp inflammation, its course, dynamics of development are usually connected with different levels of organism resistance. Processes of exudation, alteration (destruction) and proliferation prevail in clinical features.

The causes of pulp inflammation are microorganisms and different traumatic, chemical and iatric (cavity preparation, restoration, orthodontic movement, periodontal curettage) irritants.

Bacterial causes. Caries is, by far, the most common way of penetration into the dental pulp of infecting bacteria and/or their toxins. Long before the bacteria reach the pulp to actually infect it, the pulp becomes inflamed from irritation by preceding bacterial toxins. Pathosis increase, however, when the lesion reaches the depth of 0,5 mm of the pulp, and abscess formation develop when the irritation dentin barrier is breached. The acuteness or chronicity of caries as a disease serves to stimulate the production of effective irritation dentin barrier. The highly acute lesion evidently over-whelms the pulp’s calcific defense capability, while chronic lesion provides time for the development of irritation and sclerotic dentin defense. Decalcified leathery dentin might provide bacterial pathway for pulp invasion and infection. Accidental coronal fracture in the pulp seldom devitalizes the pulp at that instant. Incomplete fracture of the crown (infraction), usually from unknown causes, often allows bacteria enter the pulp. Most of the bacteria of the endodontic infection are strict anaerobes.

Iatric causes. The heat generated by grinding procedures of tooth structure is often cited as the greatest single cause of pulp damaging during cavity preparation.

Another traumatic factors: the increased incidence of pulp death following pulp exposure after wrong preparation. The advent of pin placement into the dentin to support amalgam restorations, or as a framework for building up badly broken down teeth for full-crown construction, an increase in pulp inflammation and death have been noted.

Chemical causes. To the severe insult of dental caries bacteria to the pulp, plus the iatric trauma from cavity preparations, the chemical insult from the various filling materials must be added. Silicate cements have long been condemned both clinically and histologically as a pulp irritant. The composites contain acrylic monomers in their catalyst system, and it can be assumed that the monomer would cause damage, as in the case of cold-curing resins. One could say that pulp injury from chemical irritants can best be prevented by not applying chemicals to the dentin.

Pulpal pathosis is basically a reaction to bacteria and bacterial products. This can be a direct response to caries, microleakage of bacteria around fillings and crowns, or bacterial contamination after trauma, either physical or iatrogenic. The pulp responds to these challenges by the inflammatory process.

Since the pulp histological diagnosis is impossible to determine without removing it and submitting it for histological examination, a clinical classification system was developed. This system is based on patient’s symptoms and results of clinical tests. There are next pulpitis forms to be distinguished:

I. Acute pulpitis:

- Pulp hyperemia.

- Acute circumscription pulpitis.

- Acute diffusion pulpitis.

- Acute purulent pulpitis.

- Acute traumatic pulpitis.

II. Chronic pulpitis:

- Chronic fibrous pulpitis.

- Chronic hypertrophic pulpitis.

- Chronic gangrenous pulpitis.

- Chronic concremental pulpitis.

III. Exacerbative chronic pulpitis.

IV. Pulpitis complicated periodontitis.

Chief complaints and chief clinical features. The main characteristic symptom of the acute pulp inflammation is spontaneous (i.e., unprovoked), intermittent, or continuous pain attacks. Sudden temperature changes (usually cold) elicit prolonged episodes of pain (i.e., pain remains after the thermal stimulus is removed). The pain attack arises suddenly, regardless of external irritants, sometimes provoked by chemical, thermal and mechanical irritants.

The pain differs from that of a hyperreactive pulp in that it is not just a short, uncomfortable sensation but an extended pain. Moreover, the pain does not necessarily ceases when the irritant is removed, but the tooth keep aching for minutes or hours, or days.

Pain may start spontaneously from such a simple act as lying down. This in itself explains the seeming prevalence of toothache at night. Some patients complain that the pulp hurts each evening, when they are tired. Others say that leaning over to tie shoes or going up or down stairs – any act that raises the cephalic blood pressure – will cause pain. The list of inciting irritants would not be complete without mentioning sucking and biting hot food or drink. Most often pain, however, is started when eating, usually something cold. The patient can tell which side is involved and frequently whether pain is in the maxilla or in the mandible. This may not be absolute, however, for pain, which may be referred from one arch to the other. Patients complain about aching of a maxillary molar when the maxillary lateral incisor has been found to be the offender. The patient may insist that a mandibular molar is aching, whereas examination reveals that a maxillary molar is the offender.

Pulp hyperemia. All minor pulp sensations were once thought to be associated with hyperaemia – increased blood flow in the pulp. Quite possibly, this will explain why the pain appears to be of a different intensity and character with applications of cold or heat, the cold producing a sharp hypersensitivity response and the heat producing transient hyperemia and dull pain. Pain arises spontaneously or as a result of irritant action, pulp attacks last for 1–2 minutes with large painless intervals (intermission) up to 6–12–24 hours. More often pain attacks arise at night.

Acute circumscription pulpitis. This pulpitis is characterized by spontaneous (i.e., unprovoked), intermittent, or continuous paroxysms of pain. The pain is frequently described as a “nagging” or a “boring” pain, which may at first be localized but finally becomes diffuse or referred to another area. The pain attack can be provoked by different irritants, usually the cold. Pain attack at first lasts 15–30 minutes, but with development of the inflammatory process in pulp its duration increases to 1–2 hours. Pain attacks increase and become more frequent at night. Painless intervals usually last 2–3 hours and then become shorter. Usually patients indicate the causal carious tooth, but in some cases the pain may be referred from one arch to the other.

Acute diffuse pulpitis. It is characterized by spontaneous pain and development of acute pain attack, reffered from one arch to the other and along the branches of n. trigeminus. The character of pain attack is like of neuralgic attacks. One-two days ago the duration of pain attack was 10–30 minutes and now pain attacks last for an hour. The durability of painless intervals decreased to 10–30 minutes. Pain attacks increase and become more frequent at night and at horizontal position of patient. Usually patients indicate on the causal carious tooth, but in some cases the pain may be referred from one arch to the other.

Acute purulent pulpitis. Acute purulent pulpitis is usually a result of further development of diffuse pulp inflammation. It is characterized by the spontaneous pain and development of acute pain attack, reffered from one arch to the other and along the branches of n. trigeminus. Pain attack increases, pain becomes pulsative, continuous with remission only for some minutes. At night pain attack becomes more intensive. The pain arises and increases as a result of cold irritants (hot meals, temperature more than 37 °C). Cold irritants relieve the pain.

Acute traumatic pulpitis. The main cause of this form of acute pulpitis is careless preparation of carious cavity, which results in perforation of pulp chamber with insignificant pulp trauma by rotary instrument (burs). Enough often it occurs during acute caries course preparation of carious cavity or removal of leather decalcinated dentin during excavation. As a result a bleeding point perforation appears. Through this perforation dentist may see pink pulp.

Chronic fibrous pulpitis. Unlike the acute form of pulpitis at chronic fibrous pulpitis patients feel a heaviness in the tooth. Pain appears in reply to action of thermal, chemical and mechanical irritants, intensity of which usually depends on the location of carious cavity. At the opened pulp chamber of the tooth and on the central location of carious cavity a “sucking” in the tooth can cause a quickly passing aching pain. Unlike caries the pain at chronic fibrous pulpitis lasts 30–90 minutes after cessation of irritant action.

Chronic hypertrophic pulpitis. This form of pulpitis often develops in children and young people. Patients complain of pain and appearance of blood from the carious cavity when chewing – as a result of a trauma or a food lump or at “sucking” in the tooth. Objectively in the affected tooth there is a large carious cavity filled with fleshy tumor formation. This overgrowing pulp bleeds and is little sensitive when probing, but the area of the root canals entrance is painful. Circling around the “polypus” with a probe (determination for “area of growth”), it is possible to make sure in its connection with the pulp. The dull pain is a result of action of cold irritants.

Chronic gangrenous pulpitis. Spontaneous pain is absent, when there is perforation of the carious cavity floor. The unpleasant feeling of expansion in the tooth is the permanent sign of gangrenous pulpitis. The pain usually slowly arises under influence of thermal (hot) irritants and lasts for a short time. Spontaneous pain arises and is observed when the pulp chamber is closed and the exudates cannot flow from the inflamed pulp.

In affected tooth there is a large carious cavity filled with softened dentin. The pulp chamber in most patients is opened and filled with products of pulp disintegration with an unpleasant smell. The reaction on the superficial probing is absent. The deep probing is painful. The leathery dentin covering these lesions may be removed with a spoon excavator, often without anesthesia and without great discomfort. The pulp remains revealed, covered with a grey scum of surface necrosis. Some crown discoloration may accompany pulp necrosis in anterior teeth, but this diagnostic sign is not reliable.

Chronic concremental pulpitis. The causative factor of this form of pulpitis are denticles – calcified deposits in the dental pulp. Usually they are located in the pulp chamber or root canals. It may be composed either of irregular dentine (true denticle) or ectopic calcification of pulp tissue. Denticle is formed in teeth, located in the back (molars, premolars), most often in persons over 40 years. These formations cause the permanent irritation of nervous endings of pulp, resulting in chronic inflammation.

Patients complain of spontaneous pain and development of acute pain attack, referred from one arch to the other and along the branches of n. trigeminus. The character of pain attack is like of neuralgic attacks. Pain attacks increase and become more frequent at night and under vibration. Clinical features resemble trigeminal neuralgia. Pain attack lasts 15–30 minutes. Vertical percussion is painful and may provoke pain attack.